Architecture Schools and Monastic Cloisters

Architecture Schools and Monastic Cloisters

Learning from Nature

I have been reflecting on my summaries of Morris, Rousseau and Ruskin. As architecture is a spatial discipline I thought it would be interesting to look at the enclosure in which teaching happens.

Much like William Morris’ ‘leisure as learning’, Rousseau equates the innocence of nature with the innocence of children (not so innocent if you read Herzog on nature: ‘Ghoulish hellscape’. He saw children as natural learners, and that playing outside and forming their own opinions was more beneficial then direct teaching. Rather than reading books at an early age, it was betting for them to make things, fail and start again (echoing the iterative process of design). In summary: a child is natural learning and should be allowed to get on with it.

We should utilise a students natural state when they first come to university, their own unique interests, which, when they pursue, doesn’t seem like work at all. We start in this world as being ‘good’, so the university system should utilise and not annex certain interests and aspects of life.

Monastic Cloisters

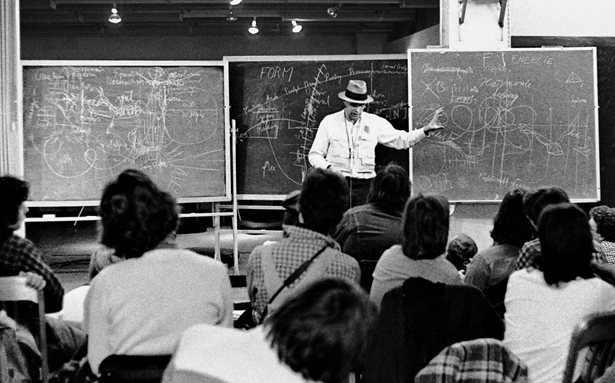

Architecture schools, particularly where I studied at the Bartlett, are the opposite of this. Due to the focus on creating a strong studio culture in order to stimulate production of work, there is a strong cohesion amongst the students, further buttressed by how the stress of working so much propagates even stronger cohesion between people in that particular discipline. While this may look beneficial on the surface, it also tends towards voiding the outside world, and students from other courses (because their is no common ground, or no time for socialising), and results in an environment similar to shuttered world on a monastic cloister — along with a similar pervasive devotion to some kind of god. While this is beneficial to religious devotion and concentration, architecture is a discipline which actively creates the ‘outside world’ and so, without ‘leisure’ (Morris) or Nature (Rousseau), how can those students contribute meaningfully to the built environment? It makes me think that perhaps multifunctional spaces are best for architectural spaces. The architectural studies building at Oxford Brookes is the antithesis of the Bartlett: a cafe, art gallery, and lecture theatre, hosting all artistic disciplines, are integrated into the studio culture. And then, the amount of work set is lower meaning that students have time for Nature and Leisure.

My ideas about how architecture should expand its boundaries have been developed from the ideas of Pascal Schöning, who stipulated that architectural education should be about everything but architecture. Further reading: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=XberDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT208&lpg=PT208&dq=pascal+sch%C3%B6ning+education&source=bl&ots=Eq0-VMY6gJ&sig=ACfU3U16hNu5we6Z870YxtIsa8Hj9DYWnA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiGuc2k7uzoAhU1oVwKHWBVBQkQ6AEwFnoECAsQKA#v=onepage&q=pascal%20sch%C3%B6ning%20education&f=false

Jack Self on the dangers of monastic working conditions: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/work-on-work-on-but-youll-always-work-alone/10002024.article