Revaluation of Ruskin and his ‘Gentlemen’: Cardinal Newman

Revaluation of Ruskin and his ‘Gentlemen’: Cardinal Newman

In my post on John Ruskin I criticised him for overusing the masculine ‘gentleman’ as a generic to describe all people. However, after reading my post, Linday Jordan recommended that I read John Henry Newman (better know as Cardinal Newman) and his alternative definition of a ‘gentleman’ (more ‘gentlemanliness’, perhaps) in The Idea of a University, published in 1854. In the chapter it’s clear that by ‘gentleman’ he’s not talking about gender or even class, but about one’s values and how one relates to the world and to oneself. I’ve added some thoughts on the text below:

‘[he] seems to be receiving when he is conferring.”

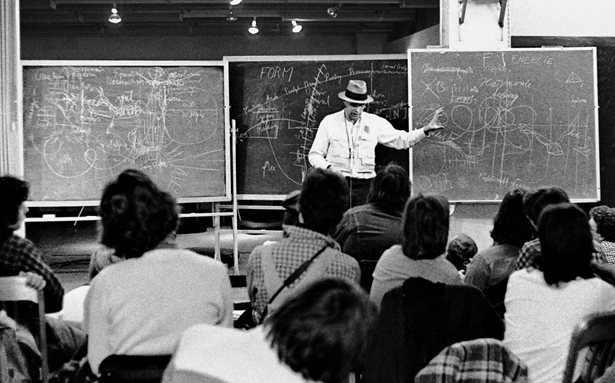

Overall, Newman’s concept of being a gentleman (Discourse 8), for both students and teachers (there is no distinction), aligns with William Morris’ opinion on the topic (see my previous post). In particular they share the same stance on the differentiation between teaching and learning. For Newman, knowing about oneself, learning oneself, and having that same level of empathy for others is vital before you release your teachings on other people. He talks of getting ones own room (mind) in order before releasing it into the realm of other people. And consequently, the university should be a collective ‘home’ where everyone feels at home.

He describes gentleman teaching in the same way the church professes to teach, and again aligns with Morris — a guide not an autocrat: ‘Hence it is that it is almost a definition of a gentleman to say that he is one who never inflicts pain. He is mainly occupied in merely removing the obstacles which hinder the free and unembarrassed action of those about him; and he concurs with their movements rather than takes the initiative himself.’

He also seems to suggest the negatives of clashing opinions (it’s here that I side more with Aristotle’s The Magnanimous Man rather than Newman), though in my own experience this in fact productive and contributes to good ideas. Maybe here it’s important that after such moments of tension it’s vital to summarise and allow everyone in the room to reach a consensus. Sine waves of emotion are needed for a rigorous debate. This kind of summary or clarity is important to Newman as to be a gentleman we shouldn’t leave questions more unsolved than we find them. I think this is particularly important in seminars and tutorials — it’s better to commit to one idea, rather than being ambiguous. I’m always aware, as I think Newman was, that our job as a teachers is stimulate students rather than impose. Often this means a teacher may be amorphous to suit, however, as I have found, students rarely do exactly as you tell them — so, it’s best to be firm and commit to one idea or task and they can always reject it or go in the opposite direction, or go beyond. With every action there is a reaction, and with every clear action there is a chance of clear reaction that easier to build upon.

A long as you can sparse the educational from the religious and saintly in Newman’s description of the gentleman there is some good guidance on how to fuse the boundary between staff and student, while making the enclosure of the university more inviting and homely. However, I do think one should consider the benefits of friction between people, or frisson as the surrealists would call it. As a case in point I will finish with a quote from Orson Welles’ classic speech (written by Graham Greene) in The Third Man:

Holly, I’d like to cut you in, old man. There’s nobody left in Vienna I can really trust, and we’ve always done everything together. When you make up your mind, send me a message – I’ll meet you any place, any time, and when we do meet old man, it’s you I want to see, not the police. Remember that, won’t ya? Don’t be so gloomy.

After all it’s not that awful. You know what the fellow said – in Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock. So long Holly.

(I’m not suggesting there should be blood.)